Smoked Volume 2: Bringing the Art of Glass Pipe Making into the Light is published by Gritcityinc., an independent publisher based in Philadelphia.

Smoked Volume 2: Bringing the Art of Glass Pipe Making into the Light is published by Gritcityinc., an independent publisher based in Philadelphia.

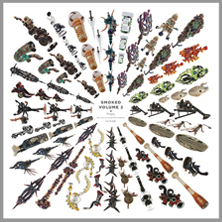

Smoked Volume 2, the second volume of independent publisher GritCityInc.‘s art book showcase of talents from the world of glass pipe-making, continues the first volume’s premise that pipe-making is fully qualified to be a part of the high-art community and also deserves to be richly documented for its freewheeling and technically expert nature. Perhaps more importantly, the works displayed in the book flaunt a brazen indifference to sharp distinctions between aesthetics and functionality and, in doing so, raise questions of their mutual limits and possible co-existence. As every “artwork” retains the ability to burn tobacco or any type of leafy substance and inhale the smoke via an aperture sometimes cleverly concealed in the form of the pipe itself, one is reassured that despite all of this aesthetic jockeying on the part of those doing the presenting, these are also objects used for getting high.

The Easy Street Gallery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, is exhibiting the pipes in the book Smoked as contemporary artworks.

The Easy Street Gallery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, is exhibiting the pipes in the book Smoked as contemporary artworks.

Many of the artists interviewed in Smoked Volume 2 express confidence that with the continued exposure of glass pipe-making, the medium will be taken more seriously. The Website for Easy Street Gallery, where an ongoing exhibition is supporting the release of the new book, claims as its mission nothing less than “to bring glass pipe making to the forefront of contemporary art.” But is this really the intent behind all of this work? Reading the many artist interviews, one finds only the repeatedly expressed indifference on the part of the pipe-makers themselves regarding the status of pipe-making.

Asked whether he considers his works “art” or simply “pipes,” Chris Carlson responds: “Both. I don’t automatically call my non-pipe stuff “art” and I definitely don’t exclude pipes from that category.” Which is to say, he doesn’t see pipes as not counting as art, but at the same time seems to have no problem if their exact identity remains hazy.

In response to the same question, Kristian Merwin replies: “Art pipes. Why can’t it be both?” And in fact, this is exactly right. Whether the pipe is made to be used or primarily made to be looked at, whether it is found caked with resin and grime on a stoner’s kitchen table or pristinely mounted in a museum (or a Brooklyn gallery with some museum-like flourishes), a pipe remains a functional object. Even if a pipe were to achieve a level so aesthetically advanced that it couldn’t be used for smoking, it would retain its reference to a functional sphere, to use-value. However, every pipe in the book could be smoked, an important aspect to the work shown at Easy Street Gallery as well.

The blending of the functional and the aesthetic worlds is inevitable here and, to my mind, something to celebrate. (Isn’t there enough non-functional detritus everywhere around us, and not just in contemporary art?). Visiting the exhibition in Brooklyn, some of the pipes can be appreciated as art-objects. While not every borosilicate creation transcends the format of a “cool-looking thing made of glass,” some works shoot for high-art conceptualism, while many others occupy a space somewhere in between the two.

J.A.G., Manafesta, 2009. Borosilicate glass. H 6, W 6, D 12 in.

J.A.G., Manafesta, 2009. Borosilicate glass. H 6, W 6, D 12 in.

Case in point is conceptual standout J.A.G., whose piece Manafesta (2009) consists of dozens of green pill-shaped pipes (inscribed with bags of money) inside an oversized glass prescription bottle with a fake prescription sticker made out to “Weezy F. Baby”, moniker of rapper Lil Wayne (himself a very public weed-smoker). Riffing on the reassuring typography of pharmaceutical packaging, one senses a reference to Damien Hirst’s “Pharmaceutical” series of canvases and installations from 2004-2005.

Other highlights include Crossroads #1 by Micah, a pipe shaped and colored like a trumpet, but an ethereal, winding one, the sort of brass that an Olympian god might play (or smoke with), and Chad Goodpastor’s “Ice Cream Cones”, a work which plays with the same sort of glossy aestheticization and de-naturalization of food that preoccupied artists like Claes Oldenburg, but unlike Oldenburg’s giant hamburger or ice cream cone smashed into a building, Goodpastor’s cones retain their function as pipes even as they play with the notions of aesthetic desire and non-usefulness.

Chad Goodpastor C.V.S., Swirl Ice Cream Cone, 2009. Borosilicate glass. H 6, W 3, D 3 in. (each)

Chad Goodpastor C.V.S., Swirl Ice Cream Cone, 2009. Borosilicate glass. H 6, W 3, D 3 in. (each)

These works stand alongside a handful of seemingly anime or comic-book inspired pipes that don’t say much beyond the aforementioned ‘cool’ factor, and form a general sense of banality that undercuts some of the more fascinating pipes. However, as several of the interviewed artists suggest, pipe-making remains an emerging scene that has evolved quickly and continues to do so. My favorite feature of this evolution is that it isn’t going in one already-defined place: pipe-makers aren’t collectively shooting for the MOMA or the coat-pockets of high-schoolers. What they are doing is exploring a space outside the typical confines of contemporary art – one in which craft, function, and aesthetics blend gleefully, sometimes in tension, sometimes harmoniously. Here’s hoping they don’t agree to a general program anytime soon.

—Lee Gaizak Brooks