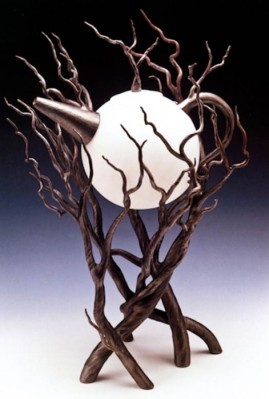

David Gignac's Celestial Teapot, in glass and steel, is part of the Kamm Teapot Foundation's extensive teapot collection.

David Gignac's Celestial Teapot, in glass and steel, is part of the Kamm Teapot Foundation's extensive teapot collection.

David Gignac’s Celestial Teapot, at left, demonstrates how a familiar object can become something otherworldly — a glass orb of a teapot re-envisioned as the moon rising over the spindly branches of a steel tree. Perhaps such transformative possibilities are what gallerist and critic Garth Clark had in mind when he wrote in his book The Artful Teapot (New York: Watson-Guptill, 2001) that the “teapot is simply one of the most potent of domestic icons.” Gignac’s teapot belongs to the renowned collection of Sonny and Gloria Kamm, a collection that currently numbers around 10,000 objects made of ceramic, glass, and other materials. It’s also a collection currently in search of a permanent home, since plans to build a new museum in small-town Sparta, North Carolina, have fallen apart. The mission of the existent Sparta Teapot Museum of Craft and Design, for its part, has also demonstrated transformative possibility: the institution functions today as a gallery that celebrates regional crafts in a broader sense, rather than as the repository for the Kamm Teapot Foundation’s collection.

This all seems complicated, especially given that, for the time being at least, offices for the Sparta Teapot Museum and Kamm Teapot Foundation are physically adjacent to each other in Sparta. As Mary Douglas, curator for the Kamm Teapot Foundation, notes, “Originally, there was a formal agreement between the two parties to get the teapot museum off the ground, so to speak”—based on the idea that teapots would be available to the museum through long-term loans from the foundation. When complete funding for a new 30,000-square-foot space did not materialize, the agreement was essentially voided, and what had been presented as a “preview gallery” for the larger museum became, in effect, the museum. (For a helpful summary of the museum’s back story, see the Los Angeles Times’ article here.)

The relationship between the two institutions, the museum and the Kamm Teapot Foundation, remains cordial, warm even; it’s just that the visions of each have taken them in different directions. As Cynthia Grant, director of the museum, explains, “What we decided to do was to stay focused on this wonderful gallery that we have and to continue to do changing exhibitions.” These exhibitions have frequently included loans from the Kamm Teapot Foundation. The Kamms are disappointed that the Sparta project did not turn out as hoped—as Gloria Kamm says, “We’re sad for them”—but at the same time are excited by the prospect of situating their collection at an institution that has an established framework in place. As Sonny Kamm explains, “We’re starting with the proposition that the entire collection would go to one place.” Accordingly, the Kamms have been meeting with museums around the country to find an institution that can offer the collection “a significant display” in addition to some sort of research center specializing in teapot scholarship.

Once the collection has found a base, it will be interesting to observe the reception of the teapots, a group of objects, which as types are often labeled as examples “craft” or “design,” that centers on interlopers from the fine arts. Many of the collection’s standouts bear names that are more readily associated with non-craft media: Lichtenstein, Haring, Sherman, and so on. A 2002-04 traveling exhibition of 250 of the Kamms’ teapots titled The Artful Teapot was, according to Douglas, incredibly successful, and this success seems likely to continue when more of the collection can be seen. As yet another manifestation of an “archival impulse,” a teapot collection of this scale may seem excessive, but it’s the excess that gives the collection such potential. It may one day become a sort of archive, the place for not only “teapot artists” or “teapot designers” but also artists and crafters to visit when searching for precedent or inspiration.

–Analisa Coats Bacall