Judith Schaechter at the opening reception, Friday, May 11, 2012.

Judith Schaechter at the opening reception, Friday, May 11, 2012.

As the sun moved lower into the early evening sky last Friday evening, the historic Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia opened its doors to throngs of art patrons who had gathered for a reception to celebrate several site-specific installations, including one of the most ambitious of Judith Schaechter‘s career. The soft late-day light filtering through the fortress-like 19th-century stone walls provided the perfect intensity of illumination for Schaechter’s 17 stained glass windows which she installed in three cell blocks of the former prison, originally built by prison reformers as a place of sanctuary for quiet contemplation and rehabilitation of prisoners before it was discovered that such solitude led to mental breakdown.

Light filtered down from a narrow aperture in the ceiling in some cells, narrow enough to prevent escape but allow a rare bit of natural daylight to filter into the tomb-like cell.

Light filtered down from a narrow aperture in the ceiling in some cells, narrow enough to prevent escape but allow a rare bit of natural daylight to filter into the tomb-like cell.

Titled “The Battle of Carnival and Lent,” the narrow glass skylights and windows that make up the completed project are the artist’s response to the unique atmosphere of the decaying prison, in Schaechter’s own words “addressing in a non-religious way the psychological border territory between ‘spiritual aspiration’ and human suffering” through scenes that are squeezed into the narrow confines of the window apertures, designed to prevent inmates from squeezing through. The peeling paint and leaking walls of the site make for a unique atmosphere to view Schaechter’s sometimes-darkly themed work, a contrast to the typical setting in a brightly lit gallery or museum.

The GLASS Quarterly Hot Sheet caught up with Schaechter at the Philadelphia opening, where a constant stream of fans and well-wishers greeted the artist and shared their effusive praise for her accomplishment. “The thing I think was most validating were comments about how the work interacted with the architecture,” Schaechter told the Hot Sheet in a follow-up interview. “One person cited how well the work complimented the original stained glass work. Of course there is no original stained glass —it’s all mine.”

Area restaurants set up sampling tables in the hallway, providing tasting opportunities in between visits to individual cells.

Area restaurants set up sampling tables in the hallway, providing tasting opportunities in between visits to individual cells.

With the work divided between three areas of cells, there was a variety of settings to experience the unique imagery, but perhaps none was more appropriate than the leaky cell in block 14 where a puddle on the floor could have been made of tears of those left behind by the penal system when someone is sent off to prison, a theme of this particular installation. One viewer’s experience was particularly moving to Schaechter. “An artist I know was really getting into looking at Daughter and Mother, two works in cell block 14 that are in a leaky double cell with a puddle on the floor that picks up their reflections. Anyway, while she was looking at the crying figure in Daughter, she felt a drop of water fall on her and this really made the work resonate… “

A panel from the “Myth of Icarus” series by Judith Schaechter.

A panel from the “Myth of Icarus” series by Judith Schaechter.

In cell block 11, the myth of Icarus is played out in three windows of images of birds, man, and a hand pointing at a wing. The center point of the exhibition is also in cell block 11, the work for which the exhibition was named. The Battle of Carnival and Lent, a stained glass work second in size only to Schechter’s panel at the Museum of Arts and Design. It takes its title and subject matter from a work of a similar name by Pieter Breugel the Elder.

The Battle of Carnival and Lent is the second-largest work to date by Judith Schaechter. (The largest is her panel at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City).

The Battle of Carnival and Lent is the second-largest work to date by Judith Schaechter. (The largest is her panel at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City).

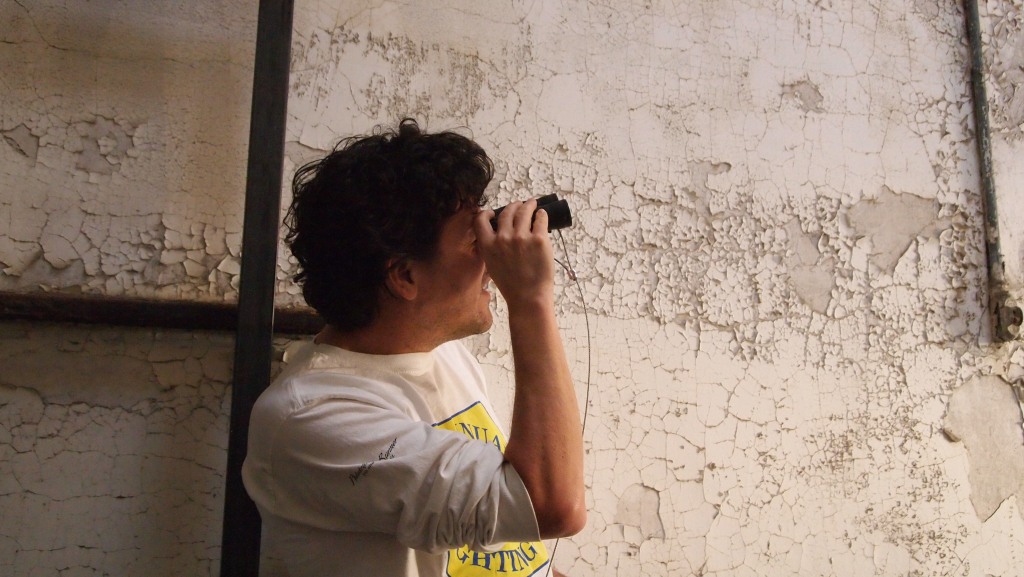

Schaechter’s 55-by-56-inch work was displayed above a door to the prison yard and a viewing bench was situated approximately 18 feet from it on a raised platform. For those observant enough to notice, two sets of binoculars were discreetly available to look at the rich details and faces of the assembled characters, a literal battle between monks and clowns. With 96 figures, the artist terms the ambitious project as “an act of hubris” and one that was “punished by the gods,” in an audio commentary posted on the Eastern State Penitentiary’s website.

Two sets of binoculars are available to the public for close-up viewing of the work for which the installation is named.

Two sets of binoculars are available to the public for close-up viewing of the work for which the installation is named.

Judith Schaechter“The Battle of Carnival and Lent”Through November 30, 2012Eastern State Penitentiary

www.easternstate.org