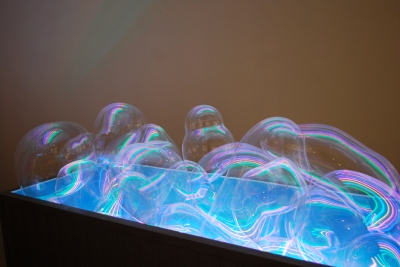

Hiromi Takizawa, Shipping from California, 2009. Blown Glass, Neon, Wood.

Hiromi Takizawa, Shipping from California, 2009. Blown Glass, Neon, Wood.

Hiromi Takizawa’s mixed-media installations rely heavily on glass. With her work appearing in two group shows next month, Takizawa traces a thematic fixation of the artist: her cross-cultural experience as a Japanese woman in the U.S., separated by an ocean from her family and country, sifting through the kaleidoscope of West Coast American life. This personal narrative features prominently in the descriptions of her works — in titles such as Crossing the Pacific Ocean (2007), Shipping from California (2009), Parallel Lives (a reference to Takizawa’s twin sister in Japan) and in her method that Tazikawa calls “cultural self-portrait”: a work that attempts to give materiality to a moment or scene of cultural identity, cultural displacement. These cultural self-portraits are precarious, unstable, fragile, suggestive of a emptiness that is tenuously filled, but always retaining a constitutive lack. In her lighter moments there is also a dreamy playfulness.

Hiromi Takizawa, One Thousand Halos, 2010. Glass, wire.

Hiromi Takizawa, One Thousand Halos, 2010. Glass, wire.

Some of Takizawa’s best work is a combination of both playfulness and precariousness, such as One Thousand Halos (2010), a work consisting of 1,000 glass shard rings hanging on a wall (and which will be on display at the “Transitions” exhibition at the Robert Lehman Gallery at UrbanGlass in Brooklyn from September 15th to December 23rd, and next year at the Bertha & Karl Leubsdorf Art Gallery in New York City). In addition to the visual curiosity provoked by the rows of wires and glass halos, the work references a temple in a Japanese imperial court dating back to the 12th century that contains 1,000 statues of Buddha, each adorned with a halo around the head. Takizawa aims to communicate her own experience in this temple, explaining in the proposal for the work that in stepping into the room full of haloed Buddhas, “I felt the weight of our history. My goal is to translate this physical and emotional experience into a concrete materiality such as I experienced in the room.” What counts here is the blend of materials, a shared, public symbol (the halo, ubiquitously “holy” in both Eastern and Western traditions) and a private emotion that wants expression.

From this mixture of elements, Takizawa shows a high level of conceptual sophistication, which, to me, discloses a certain tension between the artist’s private world and the public, shared associations of cultural symbols and materials. For example, the aforementioned Crossing the Pacific Ocean not only captures the viewer’s eye with a neon airplane exuding an eerie, solemn blue, reflecting on blown glass bubbles packed tightly together on the floor, it also deftly conjures a sense of helplessness in the face of an ominous, mysterious power (illustrated by the neon airplane) that touches everything below it (its reflections). In this way it feels to this viewer indicative of a contemporary culture whose forces (be they political, economic, celebrity-related, and so on) are too big to grasp, but impossible to avoid. In a public imagination still saddled with the memory of 9/11, the airplane cannot help but remind viewers of an attack that we were collectively helpless in the face of, glued to our televisions, the plane reflections like the indelible imprint of a trauma exposing our unpreparedness and incomprehension.

Hiromi Takizawa, Crossing the Pacific Ocean, 2007. Blown glass, neon, wood.

Hiromi Takizawa, Crossing the Pacific Ocean, 2007. Blown glass, neon, wood.

But Takizawa frames the work this way in a statement accompanying the work: “I am fascinated by the visual phenomenon that occurs when light transmits, reflects, and/or refracts on/in/through glass. I integrate these optical phenomenon [sic] with my personal narrative: by using “the-perceptional-shifts” that only the quality of glass it-self can generate, I transform my emotions into concrete materiality. The visual conversations in the work express certain cultural aspects inherent in my Japanese heritage, and in my daily encounters with Western culture. This experience adds to the awareness I have of my identity, and reminds me of my cultural heritage, it as well raises the question of where I might belong.”

Interestingly, Takizawa’s own fascination seems to begin at the level of pure materiality — in the transmission and reflection of light onto and through glass. The artist’s working method is to combine these qualities with something completely subjective, and, indeed, something that may not at all be present in the work to a viewer. Yet this merging of material and subjective experience produces conceptually intriguing work that does not need either the “inherent beauty” of glass and light or intimate personal details to stand on its own. It is therefore a synthesis that produces a third term, the finished work full of shared associations, that was not directly contained in the first two terms – which is all the more compelling since the third term may not even be intended by the artist and may be only tangentially related to that intention, if at all. This of course raises the question of the role of the artist’s intention in the experience of the work of art, and specifically reminds us that the process of creation and the experience of reception can be only partially and incompletely linked, with a gap between the two that simply cannot be brought together.

Yet this particular gap is so much like the lack felt in Takizawa’s works themselves that both may amount to two sides of the same phenomenon. In the artist’s intention, driven by the communication of private emotions, the personal import will necessarily fall short for the viewer – subjective sensations can never be made fully public. At the same time, this very failure produces imagery that is fully public, and which, for all that, contains very private associations. The neon airplane’s suggestiveness of 9/11 is exactly this sort of image: an association that many viewers will recognize in the sense of a shared symbol, a kind of “we were all there” connectedness, and yet every viewer will have a private memory associated with it. The work’s evocations of a mysterious (even strangely “mystical” in a very contemporary sense) force can be recognized in a public way, all while reminding viewers of their own memories.

This is analogous to the expression of cultural displacement: a private sense of non-identity, of homelessness, articulated in a way that can never make up the difference between feeling lost and feeling at home. The art is the stage of this perpetual struggle for identity that is precisely a struggle between a private past and a public persona, between subjective experience and a shared world of meaning.

Hiromi Takizawa, Fly Away, 2008–2009. Glass, thread, plastic, metal.

Hiromi Takizawa, Fly Away, 2008–2009. Glass, thread, plastic, metal.

And this is precisely the hybrid style that Takizawa intentionally cultivates through her method of merging material and emotion. The result for the viewer, I think, is public conceptual content. In Fly Away (2008-09), a work (pictured at right) that will be featured in a September exhibition at the Box Gallery in Costa Mesa, California, the artist substitutes glass balloons for rubber ones, thereby introducing an aura both familiar and foreign to an everyday object. The glass effectively “captures” the youthful whimsy of balloon, crystallizes it, turns it into a not-so-fleeting (or floating!) object of reflection. On the strings of the balloons are little figures, birds and trees, alternately hanging on for the ride or attempting to keep the balloon grounded. It is a rather comprehensible tension — between movement and stasis, the frozen memories of childhood and their distance in the past, their ultimate foreignness — and one that can be gleaned without recourse to Takizawa’s own story of her Japanese childhood, but equally could not have been created without that story.

—Lee Gaizak Brooks

IF YOU GO:

“Transitions: Artists of UrbanGlass” Group Exhibition (Jane Bruce, Victoria Calabro, Joseph Cavalieri, Eunsuh Choi, Kanik Chung, Kelsey Harrington, Adam Holtzinger, Michael Janis, Solange Ledwith, Yuka Otani, Pamela Sabroso, Hiromi Takizawa, and C. Miguel Unson) September 16 – December 22, 2010 Opening reception: Wednesday, September 15, 2010, 6 – 8 PM The Robert Lehman Gallery at UrbanGlass 647 Fulton Street, third floor Brooklyn, New York 11217 Tel: 718 625 3685Website: www.urbanglass.org ————————————————

“The Icarus Paradox“ A group exhibition (Glenn Arthur, Ted von Heiland, Travis Raymond, Hiromi Takizawa) September 18, 2010 — November 5, 2010 Opening reception, September 18, 2010, 7 – 10 PM

The Box Gallery 765 Saint Clair Costa Mesa, California 92626 Tel: 714 724 4633 Website: www.boxboxbox.com