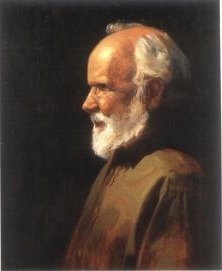

A self-portrait of the late Thomas Buechner from his 2000 book on painting. He was a serious figurative painter who devoted the last decades of his life to portraiture.

A self-portrait of the late Thomas Buechner from his 2000 book on painting. He was a serious figurative painter who devoted the last decades of his life to portraiture.

UPDATED 06/15

Thomas Buechner, the founding director of The Corning Museum of Glass and a key proponent of Studio Glass during its early decades, died on Sunday at his home in Corning, New York, at the age of 83. In the acknowledgments to his book How I Paint (2000, Abrams), Buechner described his life as “one long, glorious museum field trip,” reflecting his decades of work at arts institutions, most notably as the first director of The Corning Museum of Glass, a position he held for ten years. He was also director of the Brooklyn Museum from 1960 to 1971, and, in 1972, returned to Corning, becoming president of Stueben Glass (which Corning sold in 2008), chairman of the Corning Glass Works Foundation, and president of The Corning Museum of Glass. He also helped to found the Rockwell Museum in 1976, and served as its president for ten years. In 1985, he became a vice president at Corning Glass Works.

Born in New York City in 1926, Buechner studied at Princeton University, the Art Students League of New York, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, as well as with painter M.M. van Dantzig in Amsterdam. After he became involved in glass, Buechner became a fixture at Corning, where he worked to raise the profile of glass nationally. He founded both the Journal of Glass Studies and the New Glass Review, and wrote the glass section of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Among his numerous honors for his work in glass, Buechner was presented with the “Service to the Field” award by UrbanGlass in 2006.

“Tom always had a sense that glass was ‘no-kdding’ art,” remembers James Houghton, chairman emeritus of Corning, Incorporated, and the company’s CEO for 16 years. “Up to that point, there were a lot of people in the art world who thought glass might be a nice craft, but it wasn’t an art form in itself. Tom knew otherwise.” Houghton calls The Corning Museum of Glass the best in the world, and says simply: “Tom did that.”

“Tom set the agenda for the museum, and it was a very good one,” said David Whitehouse, currently the executive director of The Corning Museum. “His great emphasis was, as you can see from his starting of New Glass Review, as well as his exhibitions ‘Glass 1959‘ and ‘New Glass: A Worldwide Survey,’ ... fostering contemporary glass as a medium for making art, and his contribution was enormous. At the same time, he established the Journal of Glass Studies, now in its sixth decade of publication of scholarly work in glass, and so we see he was also pushing scholarly research on glass.”

Throughout his career, but particularly in the last decades of his life, Buechner was also focused on figurative painting, a pursuit he devoted himself to full-time from 1986 onwards, and which he called “the focus of my life” in his introduction to How I Paint. His paintings were exhibited throughout the United States in solo and group exhibitions, and can be found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Tom Buechner, pictured in his studio surrounded by his paintings, from the opening page of his artist's Website.

Tom Buechner, pictured in his studio surrounded by his paintings, from the opening page of his artist's Website.

Buechner’s portraits combine meticulous painting technique with a stark, somewhat confrontational quality. In a 2007 article appearing in the Smithsonian magazine, Buechner stated that he preferred to paint single individuals over mixed and group portraits, explaining that such an approach “enables me to focus on one thing at a time, separating design and form and color into three successive stages.” In order to heighten this emphasis on the singular, Buechner liked to place those sitting for portraits “alone in dark, empty space.” On this strategy, he remarked: “Have you ever hung a piece of black velvet behind you and looked at yourself in the mirror? We are each of us quite alone, and that’s what I try to paint.” Buechner’s style led him from patient craftsmanship to emotive power, blending in one unified style both the technical and the existential.

Buechner was also an intellectual, and author of several books, including Norman Rockwell, Artist and Illustrator (1971), and Seeing a Life (2007) in conjunction with a retrospective of his work held at the Arnot Art Museum in Elmira, New York, that same year. Artist Dan Dailey, who called Buechner a mentor and “a generous influence” told GLASS magazine that he thinks of Buechner every time a new issue of the New York Review of Books arrives in his mailbox, a subscription he took out at his suggestion.

Doug Heller of Heller Gallery said that Buechner had a life-altering impact on his own career, equating his impact on glass to that of Harvey Littleton, widely regarded as the father of Studio Glass. “Tom brought a degree of seriousness to the field that few other people were capable of,” Heller told GLASS in a telephone interview. “Tom was admired throughout the glass world and far beyond it.” Heller cited his own experience of visiting the “New Glass: A Wordwide Survey“ exhibition that Buechner conceived of at Corning in 1979 as “an epiphany.”

“I drove back to New York City in a kind of reverie for what I could do,” Heller says. “Through this show, Tom pointed me on a path and showed me the greater depth that existed in the glass world, which took me out of a provincial understanding of the material’s potential for making art.” Heller also remembered Buechner as a man possessing an understated but powerful sense of style that married Old World tradition with an unexpected flair by wearing a custom-tailored dark suit with bright red socks, for example. Summing up his thoughts, Heller said simply: “What a life!”

Artist Paul Stankard recalled that “Tom articulated fine art standards and demanded them of the Studio Glass world.” He remembers Buechner as someone who made himself available to the nascent glass community, and was impressed that he traveled to Pilchuck to teach. “Tom was always willing to give advice,” Stankard said.

According to Buechner’s longtime art dealer, Linda Gardner, who is the director of the West End Gallery in Corning, New York, Buechner continued to serve as a mentor for many younger painters, many of whom were invited to paint alongside him throughout the years. “He was a wonderful friend and a mentor to many aspiring artists,” Gardner told GLASS in a telephone interview. “His love of painting and his enthusiasm and readiness to share was an inspiration to all of those who had the opportunity to paint and spend time with him.”

Buechner is survived by his wife of 61 years, Mary, and his three children: Bohn Whitaker, Thomas Buechner, Jr., and Matthew Buechner. Matthew, a professional glassblower, owns and operates Thames Glass in Newport, Rhode Island.

—Lee Gaizak Brooks and Andrew Page

Editor’s Note: This article will be updated as we get additional comments from those who knew Thomas Buechner. Readers are encouraged to add a comment to this post below.