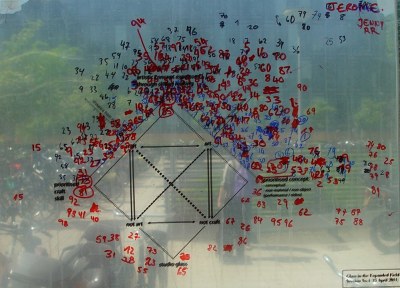

Diagram of Glass in the Expanded Field. Jerome Harrington & staff/students of Glass department at Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam

Diagram of Glass in the Expanded Field. Jerome Harrington & staff/students of Glass department at Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam

When the Studio Glass movement was launched by Harvey Littleton some 50 years ago, the phrase “glass art” was used to refer specifically to blown glass where the artist was the maker. As awareness grew of the opportunities to make sculpture from glass, the methods, aesthetics, and form remained, for the most part, rather narrowly defined. Nowadays, however, a wide array of practices is gathered under the umbrella term. Creations of glass are, in the words of the British artist Jerome Harrington, “grouped together because of their common material, not because of their aesthetic or theoretical connections.” Harrington recently set about visualizing the wide range of work and divergent aesthetics of contemporary work in glass in an effort to achieve a more nuanced understanding. His findings are intriguing, though ultimately somewhat flawed.

The irony here is that the Studio Glass movement began as an effort to modernize traditionally-held thoughts regarding glass work. Innovation is not directly discouraged, but an emphasis upon old terminology certainly dissuades it. This lack of language to adequately discuss contemporary glass is what prompted Harrington to develop, with help from students and staff at the Gerrit Rieveld Academie in Amsterdam, a bold attempt at objectively analyzing modern glass works.

Harrington was inspired by art critic and professor Rosalind Krauss, who, in her influential 1979 essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,“ stated that the purpose of “historicism” is “to diminish newness and mitigate difference.” For all our love of modern technology, art, and philosophy, we cling to the old because we remain “comforted by this perception of sameness.” Investigating the field of sculpture, Krauss felt that, in the late 1970s, contemporary terminology could not account for modern sculpture. Where once sculpture had been used as a monument for a specific site, later on sculpture very often meant a piece of art that was unrooted and could not have cared less where it was located. She declared that our need to historicize and remain within the comfortable past meant overusing the term sculpture to cover too wide a spread of topics and was denying ourselves the opportunity to discover something new.

Krauss rallied for artists, critics, and viewers to create a new vocabulary to discuss the changing nature of the craft. Her Expanded Field is modeled after a Klein Group or Piaget diagram, a tool used to analyze likeness in mathematics and psychology, respectively (see diagram), as a way to demonstrate visually and statistically her point.

Modeling his project after Krauss’s notion of the Expanded Field, Harrington set out to map the disparate glass techniques currently thrown together into one classification of “glass” because the leveling threatens to homogenize these different practices and thus break apart the entire glass world. In adopting Krauss’s Expanded Field, Harrington sets out to prove that the term glass art is being pressured to cover too vast a range of practices and works in much the same ways as sculpture. In his rendition of the Expanded Field, 100 works are selected to be charted, all made since 2000. The works were chosen from a merging of publications and web-pages. In addition, one art piece from each student is included, as well as one piece each from past and present staff members within the glass department.

The inner layer of the diagram consists of four key terms that define Studio Glass, one placed at each corner of the square: “art,” “craft,” “non-art,” and “non-craft.” The second layer creates a diamond cradle around the square with three meta-terms to describe the wide range of modern glass practices and their relationship to Studio Glass: “prioritized craft skill,” “artistic concept expressed through skilled making,” and “prioritized concept.” Two axes were also added to Krauss’s original conception: one to mark the art piece’s relation to the Studio Glass movement, the other to mark its relation to the other 99 pieces.

Harrington’s write up of the project draws particular attention to the group that he names “the outliers” the term for statistical data that lies a significant distance from the mean (majority). Harrington’s outliers rest far towards “prioritized concept,” some so far that they pass the field, a circumstance he uses to further his claim of new language for glass constructions being needed.

While Harrington’s idea of approaching glass work through this systematic approach is innovative, the project ultimately falls short for its inability to decide if it wants to be scientific or aesthetic. Harrington might desire to reach a more objective way of viewing art, but his method is not successful.

For one, the group highlighted as outliers are not proven to be outliers. Harrington neglects to mention that outliers must be mathematically proven to be outliers, which these ones cannot be, as this data is not quantitative. That is, their aesthetics and concepts are being measured, and such data that has no intrinsic numerical value. Were the object’s height or weight to be measured, hard numbers would need to be used.

Secondly, and far more importantly, the selection of the 100 glass pieces is not a true survey because the chosen subjects were not randomized. Pieces from all the glass makers involved in the project were deliberately included. This fact not only invalidates the necessary randomization of a survey, but also provokes inherent bias by blurring the line of the tested with the testers.

All of this leads to data that can very easily be skewed to prove one’s own claim. Compare this to an essay. If one were to know their thesis before any research had been performed, that writer would naturally be inclined to exclude information on their chosen subject in favor of mining only those facts which proved their point.

Like Krauss, Harrington uses the Expanded Field diagram to discuss the relationships between the elements within their chosen art field. Krauss, however, does not specifically pin each art piece down to one precise location within the Expanded Field but rather uses the diagram as a map of potential categories. She is comfortable not attempting to utilize hard numbers and instead discourses in detail on several specific works to prove her points. The classifications of her expanded field are used to expand discussion on how sculpture could and should be talked about, rather than each sculpture becoming its number. Krauss’s model was an objective method of continuing to view art subjectively – people can still have different opinions about an art piece’s purpose and relation to history, but we nonetheless need a new vocabulary in which to discuss both these changes in history and changes in our individual perceptions. Harrington’s project becomes bogged down in becoming factually accurate, simultaneously failing to see that it simply cannot be a purely factual presentation: at some point, subjectivity must intervene.

In response to my critique, Jerome Harrington said that this text is not meant to be a “full-blown research paper,” but instead “a hypothesis” that “could be ‘proved’ or ‘disproved’ by rigorous and impartial testing at a later date… First and foremost, this text aims to forward an argument.

“The term ‘outlier’ was employed for its ability to describe a particular grouping of works and to highlight the difference between these and other works situated in the large clusters; it was employed as a metaphor,” writes Harrington in an emailed response to the Hot Sheet‘s questions. “I accept that the selection of the 100 works is potentially a problem, because I selected the 100 works (no randomization, as you say). I suppose what I can say on this is that this is stage one of the project and I do have plans to develop it further – potentially working with other interested institutions.”

While Harrington’s thesis – that of needing new language to discuss new methods of glass creation – has merit, both language and art are forever evolving to discuss new concepts and to form new ways to represent those discussions, respectively. Unfortunately, such a thesis is not proved through inaccurately quantifying aesthetics, because atworks have no inherent numerical values. Such a thesis can instead be proved through observing the aesthetics as we used to, as they were meant to be observed – aesthetically – classifying through words, gestures, and perhaps even new forms of art what simply cannot be expressed through scientific data or numbers.

— Anna Tatelman

For more information on Harrington’s project, visit his project Website here.