With a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and an MFA from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn — both in painting — Amy Lemaire would seem an unlikely expert to offer insights into the flameworking world. And yet she has immersed herself in the field, where she occupies key roles as an educator, instructor, researcher, and communicator, in addition to being a practicing designer and artist. An adjunct professor at the leading flameworking program at Salem County Community College, she also leads the Bead Project at UrbanGlass, (which publishes the GLASS Quarterly Hot Sheet), where she also teaches flameworking to university students. Noting major shifts in the flameworking landscape driven by the liberalization of marijuana laws as well as technical advances in the field, the Hot Sheet recently spoke with Lemaire about her own practice, and how the scene is changing.

GLASS Quarterly Hot Sheet: How would it be best to identify you — an artist or educator?

Amy Lemaire: I see myself as located on a trade route, where there’s an exchange of technique, information, and objects, I work in my own studio, and I also work with a lot of different institutions. I’m an artist, a fabricator, a designer, a teacher, an administrator and a documentarian. I think all of this really connects to flameworking as a form because historically, flameworkers have been more mobile than those pursuing other art forms in glass. And there has always been a trade aspect, especially to glass bead making. And of course there's the constant exchange of different techniques and technologies along the way.

GLASS: To follow your metaphor, do you see yourself as a traveler or someone occupying a station along this trade route?

Amy: To me, the idea of travel is not just geographic. In my case, the travel is coming from a conceptual place as I try to make these links between different groups of people, between intellectual disciplines, and this, too, is part of how I see the trade route. Flameworking in particular is largely uninstitutionlized, and where it is, there are these pockets of intellectual activity. But for the most part it's a grassroots movement happening in a lot of different areas of the country that are connected by social media. I like to physically travel in the northeast, to be physically involved in those communities, and I try to play a leadership role when I can help share information and resources. The community is strong in technique, like Salem, where in NY, the strength might be that the studio is really open minded about forms and how to think about glass forms in the service of an idea. I'm involved with very different institutions, and I believe there is something to learn from each. That’s what I try to do, to facilitate information and resource exchange. Sometimes vocation and jobs come out of this, but it comes from an honest place trying to help people and be open-source about information.

GLASS: I've been impressed with how the glass community, facing so many technical hurdles as they started to use this industrial material in a studio setting, were one of the original open-source communities. Do you think that's true as well of the flameworking world?

Amy: I don’t think the flamework community is particularly open-source. I think we could say there’s an open-source aspect, and there's certainly a strong history of industry. But the artist and industrial communities have been working together and also fighting each other at times, and that duality is alive in our current moment. Part of that is we are talking about this grass-roots movement. The open-source parts are mostly the information available through social media where anybody can participate in the give and take of information, but we also have industry coming out of that situation in which people are manufacturing products and there’s not a lot of schools where you can go to learn techniques. There's a lot learning through an informal apprentice system, doing production work for other artists, and this is where a lot of people start learning the trade.

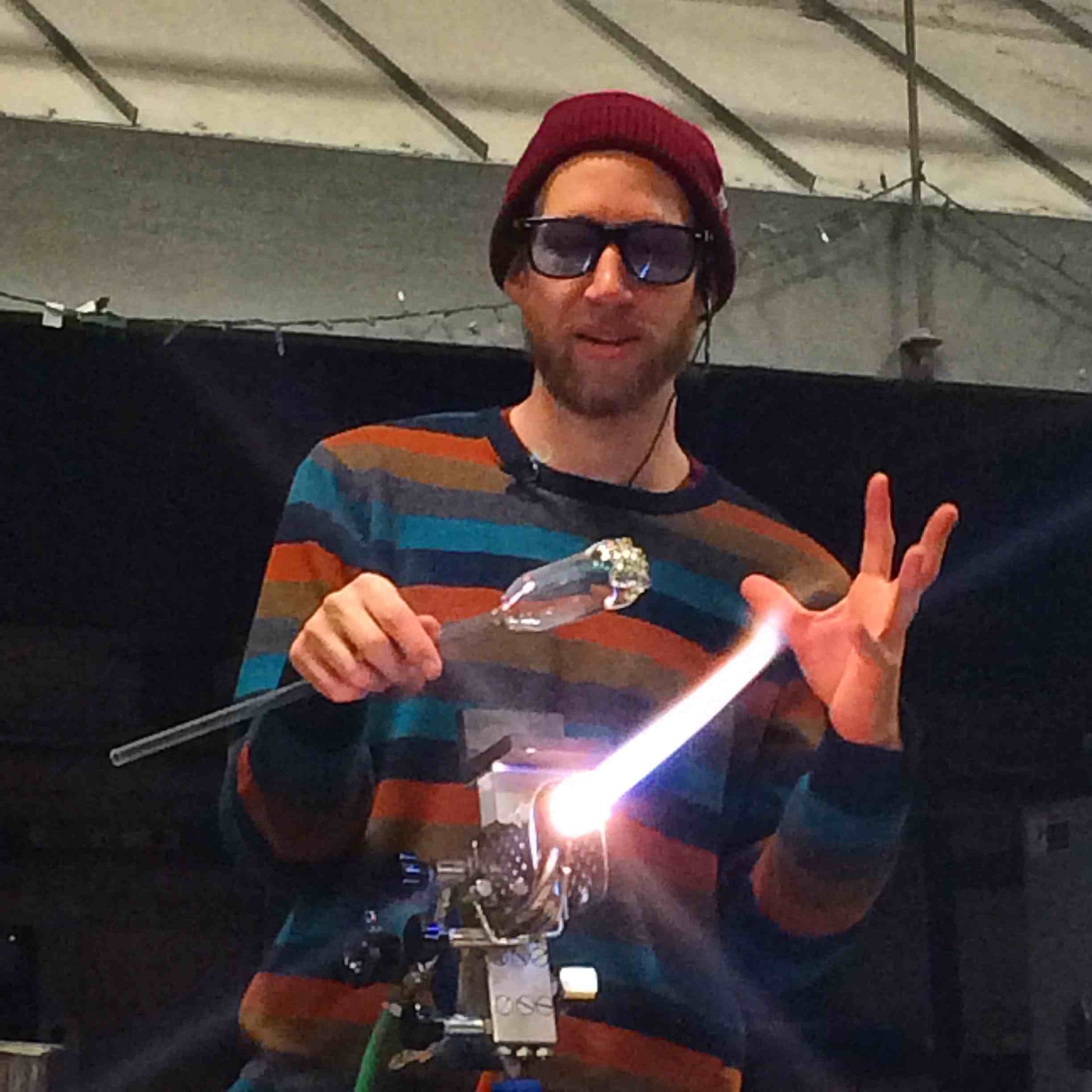

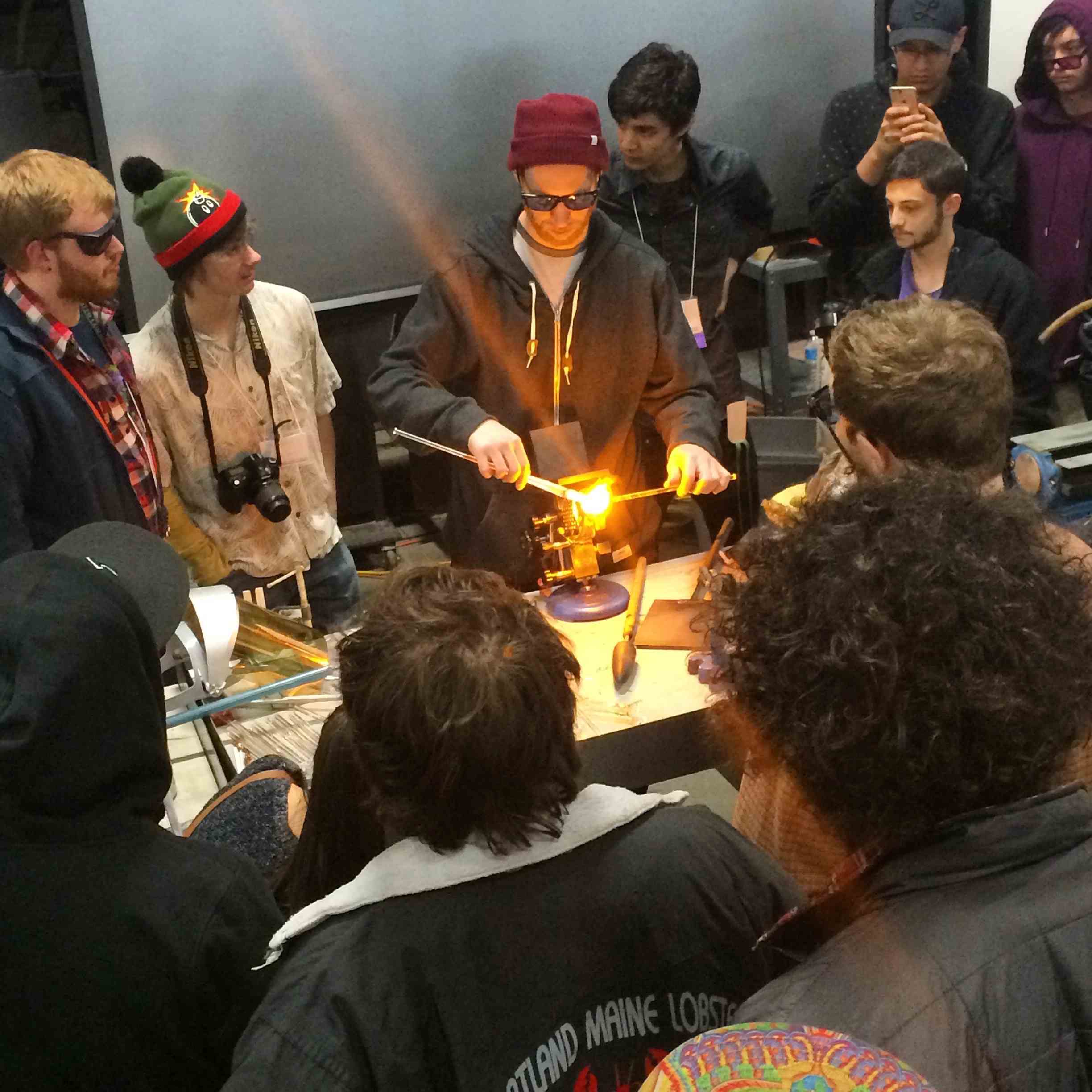

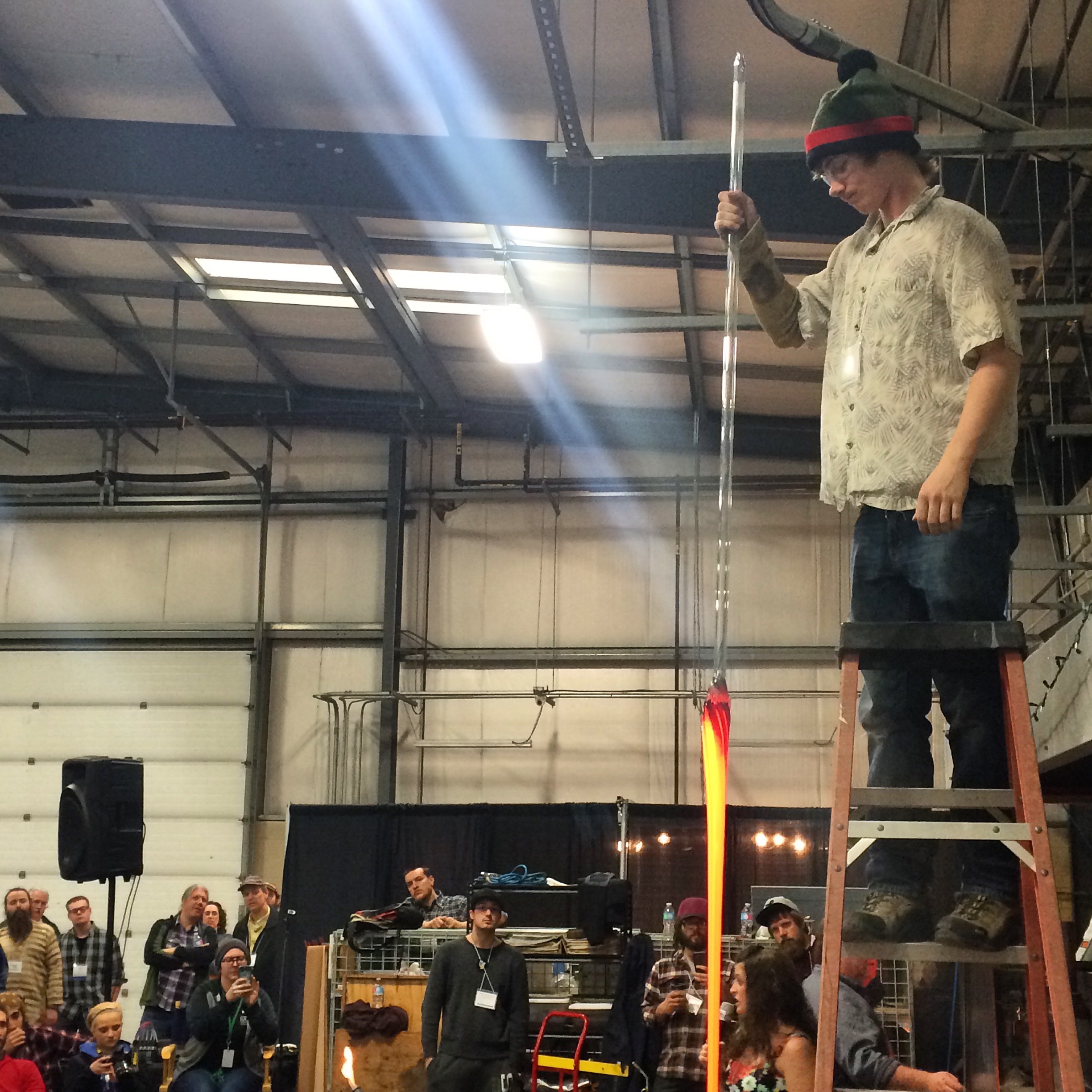

GLASS: What about the proliferation of flame-offs and other demos we've seen over the past few years?

Amy: Here is where the duality is revealed. Yes, you’re watching someone create a whole or a part of a piece, and some technical information is available, but demonstrating is different than teaching. You’re not showing them how to do it, and the artist is on his or her own how to assimilate that into their own work. if I think about open-source technology, there’s computer code available that someone can take and alter and put back out there. I don’t think in flameworking technique that it's a hundred percent out there. I would say a lot of artists do hold part in reserve to keep themselves apart. And in scientific glassblowing, if you're not involved directly in the industry, there isn't much sharing.

GLASS: What's been the effect of the trend toward marijuana legalization on the flameworking scene?

Amy: A lot of jobs are being created for flameworking that are allowing aspiring artists to learn the trade, get paid, and develop their own artistic visions while they are on the job. This has been a big plus. A lot of these news jobs, doing prep work for an artist. For example, because borosilicate color is limited in number of forms of available colored tubing, a lot of studios will do the prep in-house, and the components need to get processed into pieces. Someone has to pull down the rod to a certain size, prep in a certain way. That’s how a lot of new flameworkers are getting trained. They can also use those skills to make their own ideas develop. A lot of students of flameworking also work for other artists doing production work, some are working at scientific glass facilities.

GLASS: What's the job market like for scientific glassmaking? Haven't a lot of jobs moved overseas?

Amy: Universities have jobs making apparatus for chemistry and physics courses, and there are still jobs at places like Chemglass and other companies that manufacture laboratory glass for labs and industry. There’s some other companies like Philips Lighting that employ scientific glassblowers for certain applications. That’s where the training at Salem really comes into play, those industry-specific jobs are taught. In fact, Salem Community College's glass programs got started to satisfy needs of the local industry.

GLASS: You were involved in social media promotion of the 2016 International Flameworking Conference at Salem. I gave a lecture there, and couldn't help but notice that there was more openness to the pipe community than in previous years when I've been a speaker.

Amy: Speaking personally, and not for the school, I can say that having an open discussion about this expanding and developing industry is essential for preparing these students. Pipemaking is not permitted in the courses or studios of Salem, as is the case at UrbanGlass, but it's less of a problem than it used to be because there are more and more studios were you can go to where you can fabricate those objects elsewhere. I think that the grassroots pipe movement is still separate from the glass art world in general, though it's starting to link up. One of the things that's going to help is critical discourse. I like to try to initiate this with my peers in all spheres of flameworking because that’s going to make the objects that are created stronger. We need to develop a language that is going to help people receive these objects in a way that is honoring the artist and the creation, and is not a social taboo. I don’t think it’s the fact that pipes are functional that is keeping them from being sculptural, I think it’s the discourse informing these objects. Using the material of glass in service of the idea, and understanding how the material going to connect to the idea in a way that makes sense are key.

GLASS: How important is social media to the flameworking world?

Amy: They're incredibly important. I see another of my roles as documentarian, and I use my instagram and social media to report on what I see, including IFC. Social media is one of our modern day trade routes – a trade route that transcends geography. We need explorers, merchants, people who bring the news from place to place to share what developments are happening, what s going on. Facebook and Instagram, this is where an exchange of information happening, and critical dialogue is starting to take shape. I try to help facilitate that wherever I can, push that a little more. Just as I took over Salem's account during IFC, I'd love to have the opportunity to do that again. I will be reporting from my own account during the GAS conference this month.

GLASS: How have you seen the program at Salem addressing this shift, if they have?

Amy: I’ve been involved for the past four years, and in that short time I’ve seen a shift toward incorporating some of these functional objects into the conversation as part of a larger dialogue about the objects of an industry. There is more interest in finding the connections between functional objects, Studio Glass, scientific glass, and the larger art world —to contextualize flameworking in order to have a larger conversation. I don't think the functional industry — the cannabis industry — was really picking up that momentum until recently as we're starting to see artists maturing and creating objects that can be a part of that discourse.

GLASS: How do you see the role of education in the flameworking movement in general?

Amy: I think institutional support for flameworking is critical because it not only trains people, it can unify the history. Some have history courses, and the educational sphere is a place we can start a critical dialogue in an academic setting. This really needs to happen to further develop flameworking. And we're seeing this happen on an international level. The most recent IFC had a strong Canadian presence, the year before we had people attending from France and Japan, the year before that several people from Italy. The 2016 IFC was the best-attended in its more than 15-year of history, with over 350 attendees. I think that's partly a result of this momentum and growth we're seeing in the flameworking world, especially with the growth of the functional aspect.

.jpg)

GLASS: You're also an accomplished artist in your own right. Let's talk a bit about the fine-art side of flameworking. Are you seeing more artists trained in other materials getting interested in flameworking?

Amy: Definitely. I think it's two things really. First, flameworking in particular is very accessible for artists coming from other disciplines into glass because, like painting and drawing, there is the common ground of the line. Getting started, after developing a few basic hand skills, you can use an idea imported from another medium into glass rather quickly. At UrbanGlass, I assist in the classes with Pratt, NYU, where we've had a lot of success in student projects, they’re able to access the material working independently. You're using your elbows, hands, and wrists, unlike furnace work where you’re using your whole body. There are a lot of parallels to painting and drawing, and skills in the same realm. And when you’re teaching somebody, the sooner you can find the common ground, get the student feeling comfortable, thinking with the material, that’s when you can make a stronger connection between material and content, even if the struggle with the material is the content of the piece.

The other thing is that I've been seeing a lot of fabrication as well, particularly out of the UrbanGlass studio, where quite a few artists who want to use glass as a material choose flameworking because it seems like a good entry point to the material. It offers a way for them to get their hands on it, but also, through fabrication. We're seeing major artists outside of the glass medium hiring other artists to make their work. Borosilicate is a relatively recent development for artists and designers to use, so we’re in this magical era of exploring all those possibilities of what the material can do.

GLASS: With all your activities, do you find time for your own work in glass?

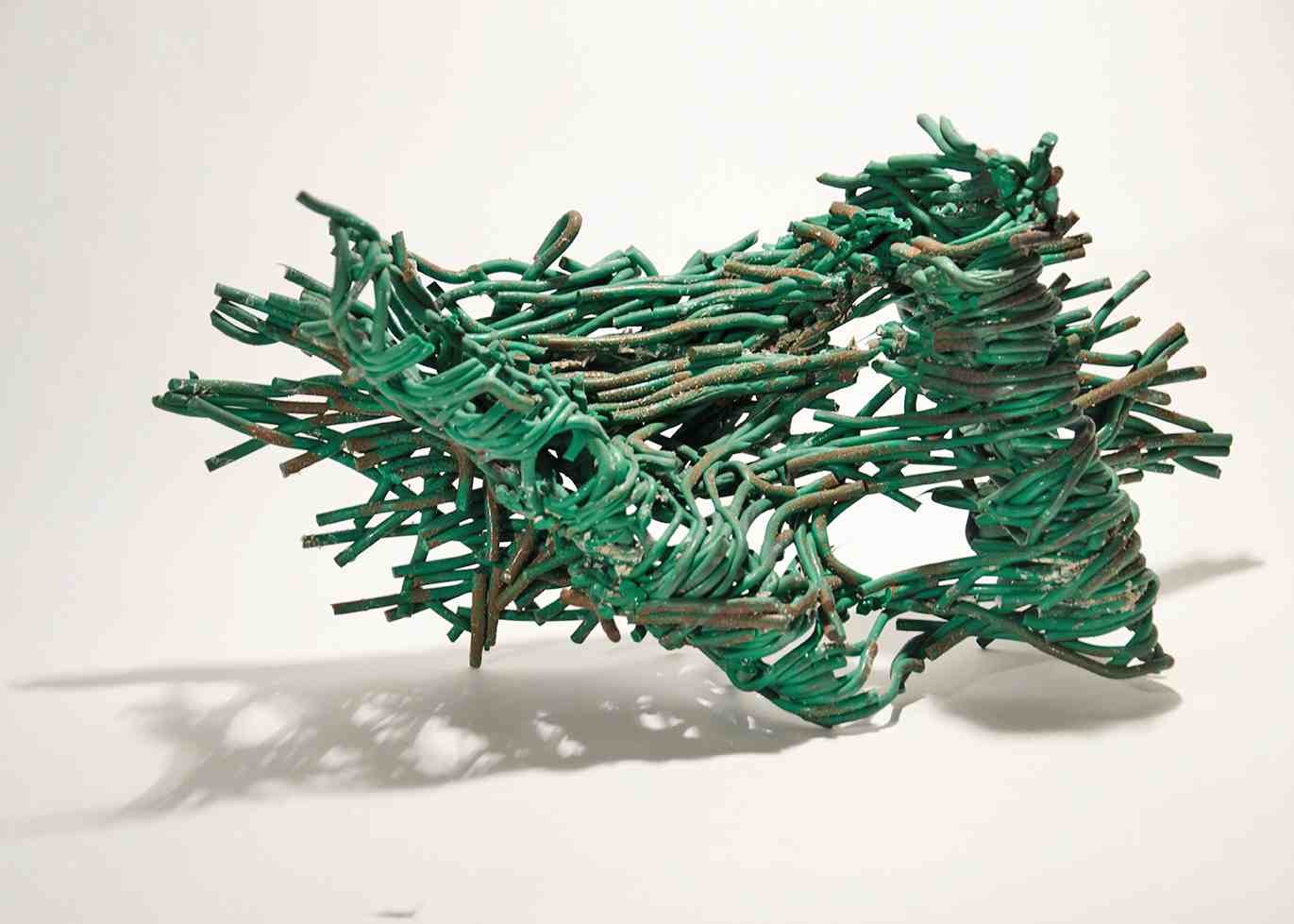

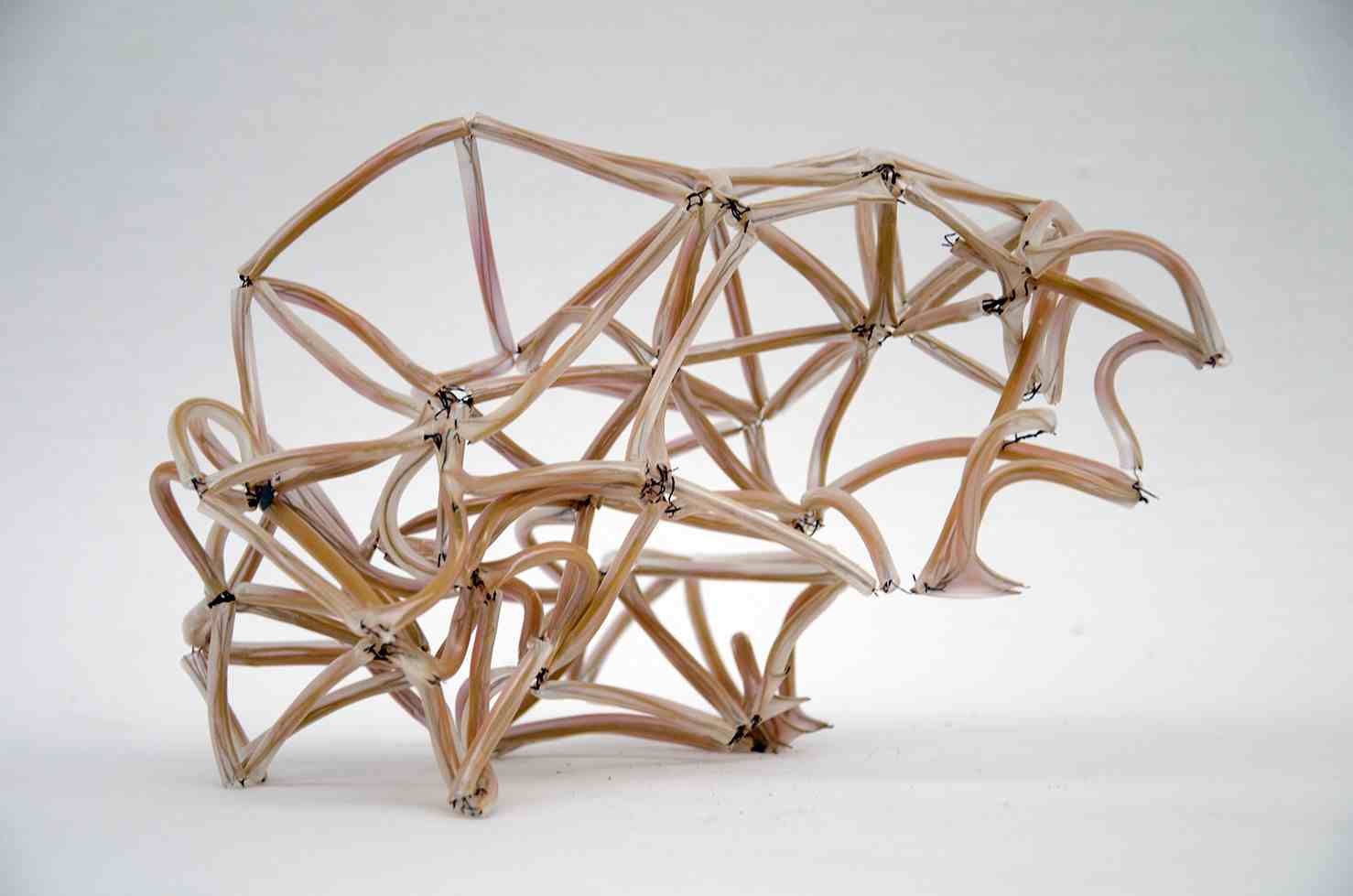

Amy: I’ve been working on a series of sculptures for the past few years, looking to create objects that help tell the story of our current historical moment in flameworking. Just as I see history as a field with lots of different perspectives, I think of the ways you can move around an object and see it in many different ways. Only through many perspectives can you achieve a full perspective. Taking the unit of the glass bead, instead of having the end point be a piece that has a relationship with the body like jewelry, or have a function with a connection to history, my sculptures explore history. I'll subject a piece to the kiln process, or a process in the hot shop. The decisions I make are completely nonfunctional but about creating a final composition that gives form to our current moment.

.jpg)

GLASS: Can you tell me about any exhibitions of your work you might have coming up?

Amy: I have a piece “Under the Bridge” at WheatonArts, a sculptural piece I made during my fellowship, and I also have a few pieces at the "Exuberance of Color in Studio Jewelry" which opens in August at Tansey Contemporary in Santa Fe. Speaking about my work going forward, I just got a new studio in New York City, and one of my new projects I’m embarking on this year is very bead-centric, I’m inspired by the old story that Manhattan island being traded for strings of beads, that’s often the story I use to engage people in the story of trading. And I was anxious to have my studio here to get a little deeper into it. Instead of having the trade route, I think of it as having a trading post. Beads have such a strong history as objects of culture, and they cut through all time periods. We're going to see a continuing history as a passport to explore all these different territories. We have artists like Liza Lou employing beads to discuss domesticity and labor, I'm very interested in communities of workers, and I use beads as a unit of currency, a trade item. There's a huge conceptual component to my bead work, which I can talk about it in terms of design, adornment, currency, and value. With all my artwork, I want to participate in commerce on different levels, and take data from one set, analyze it, compare it to another set of data, and cross-pollinate. I can't have just one structure, I have to have multiple structures, that's how my brain works.