Mark Peiser mocking up Palomar 007. The glass casting weighs about 90 pounds and is replicated by blue styrofoam. photo: cassie floan

Mark Peiser mocking up Palomar 007. The glass casting weighs about 90 pounds and is replicated by blue styrofoam. photo: cassie floan

GLASS Quarterly Hot Sheet: What are you working on?

Mark Peiser: I’m working on the seventh piece of the “Palomar” series I began in 2007. I’ve always considered thinking about my work to be part of it. Having been pretty much snowed in for the last two months, I’ve had opportunity to sort out some thoughts about the piece and series.

The “Palomar” series was inspired by the accomplishment of the 200-inch diameter 18-ton glass mirror cast in the 1930s to complete the Hale Telescope at Palomar Observatory. The astronomers wanted it to measure the speed of light and verify Einstein’s theories. Production of the mirror was considered “a vast experiment” as it was a project of completely unprecedented scale and difficulty. Corning Glassworks won the contract for casting it after all the lensmakers in the world had failed. Eventually the challenge was met and its entire surface shaped and polished by hand and by eye to an accuracy of 2-millionths-of-an-inch. It is probably the most carefully and thoroughly touched piece of glass in existence. It fulfilled the aspirations of all its creators, as did the finished telescope, which is a triumph and an icon of the mechanical age that became known as the “perfect machine.” But making the mirror took two tries.

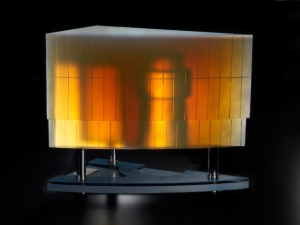

Portal (from the "Palomar" series), 2009. Cast glass with aluminum stand. H 37 1/2, W 21, D 7 in.

Portal (from the "Palomar" series), 2009. Cast glass with aluminum stand. H 37 1/2, W 21, D 7 in.

The first attempt to cast it was a disaster before the mold was full. However, the pouring was completed, and then, as another test, was annealed for 6 months. When Corning finally removed the glass from the mold, they kept the form. Though no longer useful, its overwhelming presence as an object could not be dismissed and it has been on display ever since. It is this object—the embodiment of so much labor, thought, and visions dashed and delayed—that drives this series.

I first saw the Palomar mold back in 1971, after just four years after I started thinking of myself as a glassworker. Seeing it was a powerful experience that left a lasting impression. So now, some 39 years later, I’m dealing with it from a more informed perspective on what it takes to do something new. I envisioned my series as a tribute to those and to what it takes to expand the boundaries of glass.

Rear view of Mark Peiser's Portal (2009).

Rear view of Mark Peiser's Portal (2009).

Anyone who has worked glass knows that things can quickly go south. Sudden disappointment and delayed gratification seem part of the life. We all have stories. In 1994, I wrote a piece on change that began “glass is a tough lover.” I’m aware of nothing that better symbolizes that relationship than that giant fractured disk in Corning’s Hall of Innovation. The message I see in it now is failure is part of the process. I also see that, even when flawed, there can be beauty.

Making work to honor an object whose flaws were the result of wrong choices and miscalculations presents some difficulties for the craftsman in me. When attempting the unknown, certainly any serious attempt seems laudable, but it can’t be an excuse to lower standards. It’s around this issue that my respect and vision transfers from the failed piece to the dedication that ultimately will triumph. This is the part of the Palomar story I related to most. The series is my response. I’m also aware I’m approaching it differently than previous series.

Mark Peiser, Sanctuary (from the "Palomar Project"), 2009. Cast opal glass, steel, chrome. H 16 3/4, W 10 1/4 in.

Mark Peiser, Sanctuary (from the "Palomar Project"), 2009. Cast opal glass, steel, chrome. H 16 3/4, W 10 1/4 in.

Over the years, my work has progressed more or less by assigning myself lessons. In the 1960s I taught myself to blow by inventing exercises, much as how I learned piano. I have a degree from the Institute of Design, the American incarnation of the Bauhaus where teachings stressed understanding process, using materials “honestly,” and most famously, “starting from zero.” Not a bad preparation for the reality of the glass scene at the time. From that perspective I developed a habit of assigning myself “thought experiments” about the possibilities for glass and its processes related to the implications of transparency on the nature of objects. The goal was to identify approaches that actually require or justified being made of glass, that were doable, and that might lead to beauty. Every series has had its own consciousness and approach to process and composition that defined its objects, like a genre, but not their subject. Subjects were chosen as a consequence of the approach, ideally with some metaphorical relationship to it, like a melody plucked from a harmonic structure.

Today, perhaps this all may seem over-thought or contrived, but when my involvement began glass was trying to reinvent itself and asking to be seen anew.

The Palomar pieces I see as more straightforward and obvious. They say nothing of their own process and the subject is simply a quote. They emerge by selecting an evocative sculptural element from the mirrors honeycombed geometry and presenting it in differing contexts and structures referencing various aspects of the rich milieu of its creation. Science, rivets, space, astronomers, perseverance and so forth. There’s a long list if I ever get to them.

When I committed myself to this direction in 2007, I though I knew how to make the glass elements. It took six months to find out I didn’t; nor did my friends, colleagues, the industry or literature. Thus, one of the technical challenges was to discover and develop a material process to make mold cores suitable for hot casting. The seven pieces cast so far each represents a different step towards a workable mold solution. The last piece, Portal, cast in October, was a complete success. It was a lesson that opens the door to other unique and exciting possibilities.

The piece before me now, however, was cast last April and that approach had a major problem at the glass/mold interface requiring serious, (read really awkward, hand cramping, exacting and monotonous) hand finishing. That work is largely done and I’ve moved on to developing mock-ups for its base and pedestal.

This piece, as of yet untitled is a tiny sliver of the Palomar disk at one half scale that has been edited and presented to allude to the much reduced geometries of astrolabes and armillaries. These were sort of sophisticated sun dials invented thousands of years ago for navigation and the telling of time- earlier achievements to understand and find our place in the cosmos.

GLASS: What artwork have you experienced recently that has moved you, and got you thinking about your own work?

Mark: The Tales of Hoffmann, a 1951 film by Porter and Pressberger, based on the Offenbach opera. For me every aspect of this is an inspiration- the music, the visuals, the stage craft, the film itself. It’s a unique and compelling work. Everything about it seems human and made by hand.

My work has always been inspired and informed by my background with music. Among other ways I perceive music somewhat visually, spatially and texturally, I’m responsive to sonic iterations of atmosphere such as transparency, light and color. It’s led me to wonder if music is to sound as glass is to light, and what that looks like.

Recently also I’ve “discovered” the piano music of Isaac Albeniz who could make melodies of fragments like fragrances on a summer night.

And, of course, the Olympics. You just got to love curling.

GLASS: Do you have any upcoming exhibitions you can talk about?

Mark: I’m represented on an ongoing basis by the Wexler Gallery in Philadelphia and the Ken Saunders Gallery in Chicago. Also I will have work (hopefully including the piece I’m working on) at the Habatat International Invitational opening April 24th. Also opening April 20th, there will be a retrospective exhibition, “A Life in Glass,” at Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft in Louisville that will be open during