The Covid-19 pandemic, and the shutdowns ordered around the world to control it, have forced all of us inward. With vastly more time spent sequestered in our homes, we've become intimately familiar with every inch of our living space as socialization has been severely curtailed. One artist who's spent the pandemic reflecting on how our lives have changed is exhibiting a new body of work that explores the dual themes of isolation and hope, two sides of what the Spring and Summer of 2020 has been like for many of us. Scottish glass artist and harpist Alison Kinnaird is holding an exhibition of her engraved glass tableaus at her home studio, a repurposed 19th-century church in the village of Temple, 12 miles south of Edinburgh. The exhibition was meant to be a part of the art expo known as The Edinburgh Fringe Festival, however, when the event was canceled due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, Kinnaird decided to host a solo show in her private studio space. Internationally known for her prolific oeuvre in glass and music, Kinnaird has spent nearly 50 years of her life creating art.

Kinnaird produces her work by using an ancient copper wheel engraving technique. This old-established method allows glass engravings to appear precise and delicate. “The imagery, the background, and the stories, and the cultural contrasts make a big difference in my work. Although my work is Scottish in many ways, I enjoy having regional differences as well as being able to reach out to the international audience,” Kinnaird told GLASS Quarterly Hot Sheet in the video interview. In the current exhibition, she delivers the theme of isolation and hope by consulting the influences of the global health crisis. In her new work, Kinnaird crafted a reflection on disrupted patterns of social lives and their effect on the natural environment.

Her past and new works address urban focus. Her most recent project, titled Lockdown 2020, shows a structure resembling an apartment building facade decorated with graffiti. By using the fragile medium, the artist captured the internal complexity of human drama bounded by common experiences across the world. Six windows feature lonesome figures absorbed in solitude. In nearly each opening, warm light shines on the subjects, coloring monotone figures in a yellow haze. “This piece is the most direct production of my lockdown experience, and it is a reflection of something many people might have felt,” Kinnaird commented. Her previous piece Apartment Blocks, created before the COVID-19 pandemic, shares a common theme with the Lockdown 2020. Kinnaird captures domestic situations appealing to the present context of the global pandemic. A myriad of household conflicts concealed from the public view now appears transparent in Kinnaird’s glass cubes. “The word “apartment” is a play-on term because you are apart from everybody, contained in your own little space,” the artist clarified. Human silhouettes grouped in solid blocks of glass get lost in the infinite labyrinth of reflections and refractions becoming a continued narrative as the cubes rotate. “This work is about relationships,” Kinnaird continued, “The figures are trapped in their spaces, being locked in personal situations. This context appeals to all of us from time to time.”

In her series Thresholds, the compositions are imbued with symbolic elements featuring doorways, which suggest the presence of figurative thresholds people cross throughout their lives. Heavy Caithness stone doorways hold optical glass plates engraved with handprints and figure silhouettes. Regardless of the ominous appearance, Kinnaird expressed that the doorways have potential, serving as a sign of hope for people who wish to get out. “It is not a closed-door, you can go through it. This is one reason to use glass in the doorway because of its transparent quality allowing travel through that space,” Kinnaird explained, “Doors are not shutting you in, on the contrary, doors serve as a space of transition.”

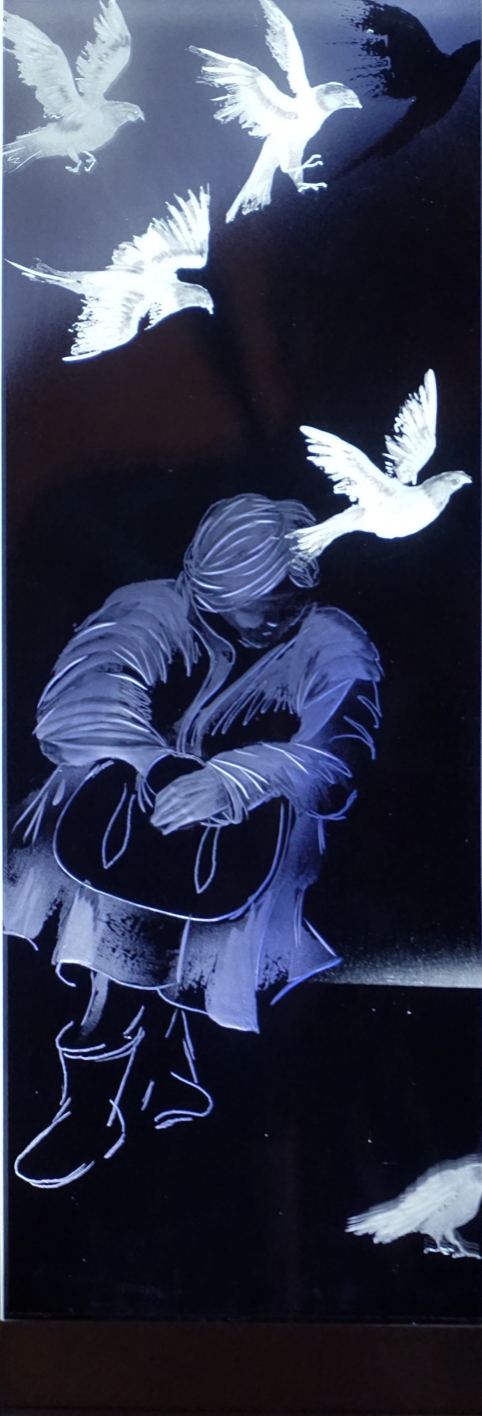

The Waiting series has developed out of the artist’s stays in New York City over the past ten years. Kinnaird treats the City as a source of inspiration, where she spent time observing and collecting images of her subject matters. “Most people are depicted alone in response to how difficult it is to find a close relationship when you live in the City,” Kinnaird noticed, “They are all waiting for something to happen, whether it is waiting for a person, a meeting, or a transport.” The series of sketches was produced without people knowing they were being captured by Kinnaird. By allowing her models to behave naturally, the artist was able to catch a candid moment in their lives, leaving herself to wonder about their identities. Other work inspired by her New York stays is Subway Photographer, engraved on a free-standing laminated glass panel. Subway Photographer is a part of the three 2019 panels series, including the works Astronomer, and Graffiti Artist. Subway Photographer shows a monotone silhouette of a man with the camera covering his face. His camera is pointing at the audience, engaging with the viewers through the illusion that he is taking their picture. The background features engraved square portraits of people, presumably the subject matters of his photographs. The majority of background sketches were conceived in the subway during Kinnaird’s trips, “Subway is a melting pot of the city,” she jested, “you can meet all kinds of people there.”

During the lockdown, Kinnaird spent a lot of time connecting with nature. She received a commission to work on a series of glass panels for the collection of the Yale University Center for British Art. Kinnaird admitted that this commission became a major catalyst motivating her to produce new work during the self-isolation period, “It was very hard to stay focused on producing something serious,” she said. Her Butterflies series are full of life and energy, sparking positive emotions in viewers. This year, Kinnaird noted more butterflies than usual in her home garden, “They are truly beautiful things,” she said, “Butterflies represent the opposite of my lockdown piece. Butterflies are flying free, escaping their trapped silhouettes. This series signifies the moment when we all can finally get out.” From the Butterflies series, The Singer allegorically shows a person’s voice disguised as a flock of butterflies, representing the song of hope. Another work directly connected to nature is the Birch Forest panels which were produced in response to this year’s natural awakening in the countryside. The piece is lit with LED multi-color lights, gently changing the palette as a sign of the seasonal changes. The panels represent the contrast between the human condition and the natural world. “It is a meditative piece, striking at the core with many visitors who have come to see the exhibition. They were in trance while watching the colors change through the seasons, starting from white, then the leaves gently turning to green, yellow, and orange,” she shared.

On the final note, Kinnaird remarked about the current conditions regarding the world’s political, economic, and ecological situations by admitting that the world is at the crisis point right now, “As an artist, you can comment on these things. You have to make your gesture and leave your input as much as you can,” she emphasized, “One of the good things about being a wheel engraver, it’s looked upon as being a dying art, there aren’t many of us around, yet the technique is not limiting our ideas.” Kinnaird affirmed herself as a devout believer in the global language of art, “The diverse cultures of all the places that I've visited are wonderful and important, and add such richness to their art. What my travel has brought home to me, is how much we all have in common, and how art can speak to everyone, no matter what their background,” she said, “I suppose it's what we are all trying to do as artists - to have other people recognize a common human experience.”

To view this virtual exhibition, use this link.