Luke Jerram at work in the Museum of Glass hotshop during his November 2011 residency.

Luke Jerram at work in the Museum of Glass hotshop during his November 2011 residency.

GLASS Quarterly Hot Sheet: What are you working on?

Luke Jerram: At the moment, I’m investigating the implications of the visualization of data. I think there’s a lot of that going on. And what it means to turn a line into three-dimensional form. It sounds a bit weird, but an example of that would be taking the 28 seconds that the Hiroshima bomb was going off. I have the sound file, and I rotated that sound file on the computer to create this … well, it looks almost like a carrot which is the only problem with it … it’s rotated on a computer to create this virtual 3-D form, then it’s printed as on a 3-D printer. I quite like 3-D printing because at no point is the human hand involved. You’re taking out any man-made element. You’re just taking data, transforming it, printing it as a three-dimensional form to create something else.

So you create these volumes that are still presenting the data but in a different way. And I suppose the question is, how does it differ from three-dimensional form and flat form? What’s the meaning of this object? I’m creating objects to contemplate the meaning of the phenomena of the Hiroshima bomb going off, but also what is this object that I’ve just made?

This three-dimensional printed sculpture by Luke Jerram is based on the seismographic reading of the earthquake that caused the Japanese tsunami. courtesy: the artist

This three-dimensional printed sculpture by Luke Jerram is based on the seismographic reading of the earthquake that caused the Japanese tsunami. courtesy: the artist

I’ve taken 9 minutes of the Japanese earthquake seismograph, and then again put that into a computer, rotated it, printed it as a 3-dimensional form, a 3-dimensional sculpture, to create this object to think about. And I suppose there’s a similarity in the work that I’m making to the glass in creating this object that is very potent because they’re very beautiful to look at but are also these sort of awful, tragic events. There’s a tension that arises between the beauty of the object and what they represent. You’re attracted to them, but you’re also repelled by them. That gives them a tension and a certain potency that’s interesting.

Luke Jerram, Swine Flu (edition of 5), 2010. Flameworked glass. H 7 7/8, W 7 7/8, D 7 7/8 in.

Luke Jerram, Swine Flu (edition of 5), 2010. Flameworked glass. H 7 7/8, W 7 7/8, D 7 7/8 in.

I look for subject matter that people care about, data that perhaps were represented in the media as well. For example, the way viruses are presented in the media or in newspapers as being brightly colored images was actually investigated further and found that viruses are really transparent forms. They don’t have any color and yet scientists are adding color. And by adding color, which they sometimes add for scientific reasons but also they are adding them just because they look pretty. So you end up with this population of people who believe that viruses are these brightly colored organisms that they’re just not. Also color has an emotional impact on people so you can make them look like these deadly organisms. But you can also make them look slightly more organic. Journalists would phone up and say, “I need a photograph for my article of some healthy bacteria,” and they would say, “Oh you need the green and white ones for the article. They look more healthy.” If they say they need deadly bacteria for the article then it’s, “Oh you need the purple and yellow ones.” They’re selling these images, and they’re portrayed as a piece of objective scientific truth and actually they’re very subjective. They’ve been made by artists. So what I’m doing with my glass sculptures is taking out that color and representing them as I think they are: three-dimensional, transparent forms. Unfortunately, I’ve replaced one problem with another. I’ve made them incredibly beautiful.

The Museum of Glass hotshop team, headed by Ben Cobb (at left), creating a giant version of Luke Jerram's HIV virus during his residency in November 2011.

The Museum of Glass hotshop team, headed by Ben Cobb (at left), creating a giant version of Luke Jerram's HIV virus during his residency in November 2011.

GLASS: Do you think that this new work might be in for the same critique? That you’re taking tragic events and making them into beautiful objects?

Luke: No. No I’ve softened it up a bit. What I’ve been looking at is taking a graph. I’ve got a graph of the FTSE 100 [an index of the largest companies on the London Stock Exchange] and I’ve got a graph of the American banking crisis, and you can see from 1998 huge growth in the stock market and when the stock market suddenly crashes in 2008. So I’m taking that data, that graph, rotating it, and turning it into a glass form. I suppose it’s a play on the economic bubble, that there’s a sort of fragility to it. We’re representing time and history and economics. So I’m making these objects, again, to contemplate that. And also, everyone in the world at the moment cares about the state of the economy, and knows the history of it. It’s a subject that people care about. It’s this sort of subject, economics and stock market value are these sort of transparent, invisible phenomena. To see it on a graph is kind of meaningless to a lot of people so I’m interested in making a different visualization of that, and people might be able to relate to it in some way.

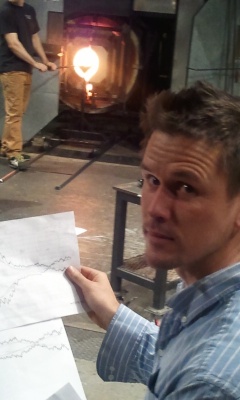

Luke Jerram consults his drawings of a graph of the American Stock Exchange, on which he based a three-dimensional vessel form, during his November residency at the Museum of Glass.

Luke Jerram consults his drawings of a graph of the American Stock Exchange, on which he based a three-dimensional vessel form, during his November residency at the Museum of Glass.

GLASS: What artwork have you seen recently that inspired you and got you thinking about your own work?

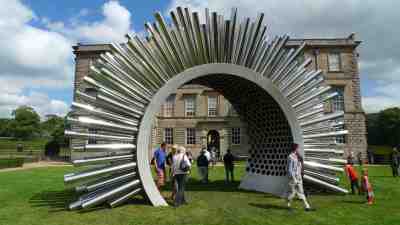

Luke: I don’t know. I suppose I get inspired from all over the place in all sorts of weird and wonderful different ways. I get inspired from traveling and all sorts of different cultures. I’ve been to Iran and spent time in the mosques looking at the use of mosaics and sacred architecture, the use of light in their architecture, and that inspired my art work Aeolus. I spoke with a desert well digger about his life digging tunnels under the ground, and he talked about how sometimes the wells he was digging would sing with howling wind. That got me on a three-and-half-year journey to make my own piece of architecture that would sing with howling wind. It’s a 6-meters-tall, ten-ton singing Aeolian wind tower. It’s touring the UK. I kind of bit off more than I can chew. You know when you kind of realize what you’ve got? I’ve got this half million pound project now, I have to deliver. I promised I’m going to deliver it to everyone, and I told you it’s going to be great. So the work I’m making here is almost kind of an antidote to that. I’m making small, intimate works that are very potent and powerful.

Aeolus, a wind-instrument sculpture by Luke Jerram, installed at Lyme Park, Cheshire, England. photo: luke jerram

Aeolus, a wind-instrument sculpture by Luke Jerram, installed at Lyme Park, Cheshire, England. photo: luke jerram

GLASS: Can you talk a little bit about your relationship to glass which, as I understand, began with the virus series and seems to be continuing in some way? What’s the nature for that material connection?

Luke: Glass is just a wonderful thing isn’t it? I suppose a lot of my work involves making visible forces visible. I made an artwork controlled by the moon. I used the gravitational pull of the moon to control water levels to create this sort of sonic artwork. I was translating the gravity of the moon into sound. Aeolus, the singing sculpture, is turning the invisible, shifting, 3-dimensional landscape of wind into music. And glass is a wonderful thing. It’s sort of there, but it’s not. It’s semi-visible, but it’s also semi-invisible. So it’s a very useful tool in that you can use it to present invisible phenomena, like the sound wave of the Hiroshima bomb going off.

It’s also this precious and wonderful thing. I suppose that, because I’m colorblind, I’m interested in optics and the way the eye works and how we see the world. Glass has an optical quality to it that is fascinating. When you hold a sphere of glass up, it’s immaculately round, and it’s impossible to see the front surface of this sphere. But it’s an optical illusion, and I’m interested in optical illusions because they reveal something about our senses and the limitation of our senses. Our eyes are just filters for the world. They enable us to see a very small section of the entire electromagnetic spectrum. So that’s one of the reasons I like glass as well. It provides an interesting opportunity to play with optical illusions.

GLASS: Where is it possible to see your work on exhibit?

Luke: I’ve had 30 exhibitions this year around the planet, but at the moment I’ve got glass work at GLASSTRESS in Venice. I understand that show is moving to the Museum of Art and Design in February of 2012. Next March I’ve got a glass show at Heller. You can find out about my exhibitions on my Website at lukejerram.com.